Gone Batty

Not quite what one anticipated seeing on a trailcam in December.

The size and pale belly suggests that this is a Natterer’s bat, a widespread but scarce species. Professional bat ecologists try to survey on nights when the minimum temperature stays above 7c or even 10c. According to the trailcam, this bat was afoot in a chilly 3.8c. At a time when most British bats are hibernating – in old mines, church roofs, cracked trees or other strange places – this one is apparently awake and hungry.

In practice, some bats do wake up in winter. They emerge to change their roosting site, seek cold insects or even engage in social interactions. It will be interesting to see if this bat reappears.

Regardless of what December may be for bats, it is extremely busy month for foxes. Their mating season arrives around New Year and many males are wandering widely. Sometimes they engage in fights with each other, but this one looks scar-free.

Foxes are not shy of using their voices but then again, neither are badgers. This does not appear to be a particularly friendly interaction.

It has been a dark, rainy winter. The footpaths are boggy and the stars generally sealed with clouds. But wildlife continues its drama in the gloom.

Words from a Hazel

The weather has turned into typical November and even going out in the garden seems to require a wetsuit. But trees are still with us, twirling leaves as their bark darkens into a glossy skin.

Many of Britain’s trees have acquired a certain cultural mystique. Hazel is not the grandest nor the most stately, but it is embedded in the framework of many small woods. It was traditionally harvested by coppicing – cutting to a stump to encourage it to sprout long straight poles – and many now assume a sprawling, many-headed presence on the woodland understorey.

And yes, squirrels use them as furniture while squabbling.

But it is dormice that are indivisible from hazel, at least if you take a traditional view. It is woven into their scientific name – avellanarius is derived from avellana, the species name of hazel – and while we now know they are more flexible in their habitat choices than previously supposed, there is no doubt that this little tree is very appealing to them. They eat the nuts, they climb the stems, and they find its leaves very agreeable for building a summer nest.

Dormice nests are more artistically composed than that of the average wood or yellow-necked mouse, which is generally just an unimaginative mash of leaves.

Foxes, too, find purposes for hazel.

It’s a little unusual to see two male foxes wander through the wood together without conflict; they are probably brothers, and cubs from this year judging from their lanky build and smooth coats. But they are outdone by the third fox, who rolls into the scent-marked hazel, biting it as she does so. I have seen foxes assault vegetation a few times but usually in the heat of an argument with another fox. They have glands around their chin and jaw and it is likely that the biting behaviour is helping to leave her scent on the tree.

Hazel itself, of course, simply gets on with the business of living, regardless of the uses that people and animals might find for it. And looking within its withering leaves now, baby catkins are waiting for their moment of glory in late winter.

Even a rainy November cannot stop the turn of the seasons.

Autumnal, Again

No words today; just a quiet wander through the season.

Autumnal

Of colours on stilled rivers.

Of artistry in the trees.

Of a stinging nettle’s poison muted by frost.

Of buzzards and their followers in cold skies.

Svalbard: The King’s Neighbours

Mid-October

No one disputes who rules the far north.

About 10% of the world’s polar bears live in the Barents Sea, and hundreds call the Svalbard islands home – some permanently, others lumbering out over the sea ice to seek seals. Black and brown / grizzly bears are old acquaintances of mine, but polar bears are altogether different: the largest and most formidable carnivoran, unimaginably restless in a realm of shimmering white.

They are not commonly seen except from boats, but they are out there, somewhere.

Wilderness is not a game, and animals are not toys. I’ve written that line many times before, because I’ve explored much of what remains of Earth’s wild corners, and while learning from them, have incidentally observed a good deal of fellow-human behaviour. The glorious, merciless mystique of Wild – of a place where decisions matter – can deepen, soften and sharpen people. Or it can provoke irrationality of a kind that is not only juvenile but often very dangerous.

That is not a new problem. But it is, perhaps, becoming more common, frequently with dreadful consequences. That is absolutely not to say that every victim of the wilderness has done something ridiculous; far from it. The tragically unpreventable and the split-second mistake will always be with us.

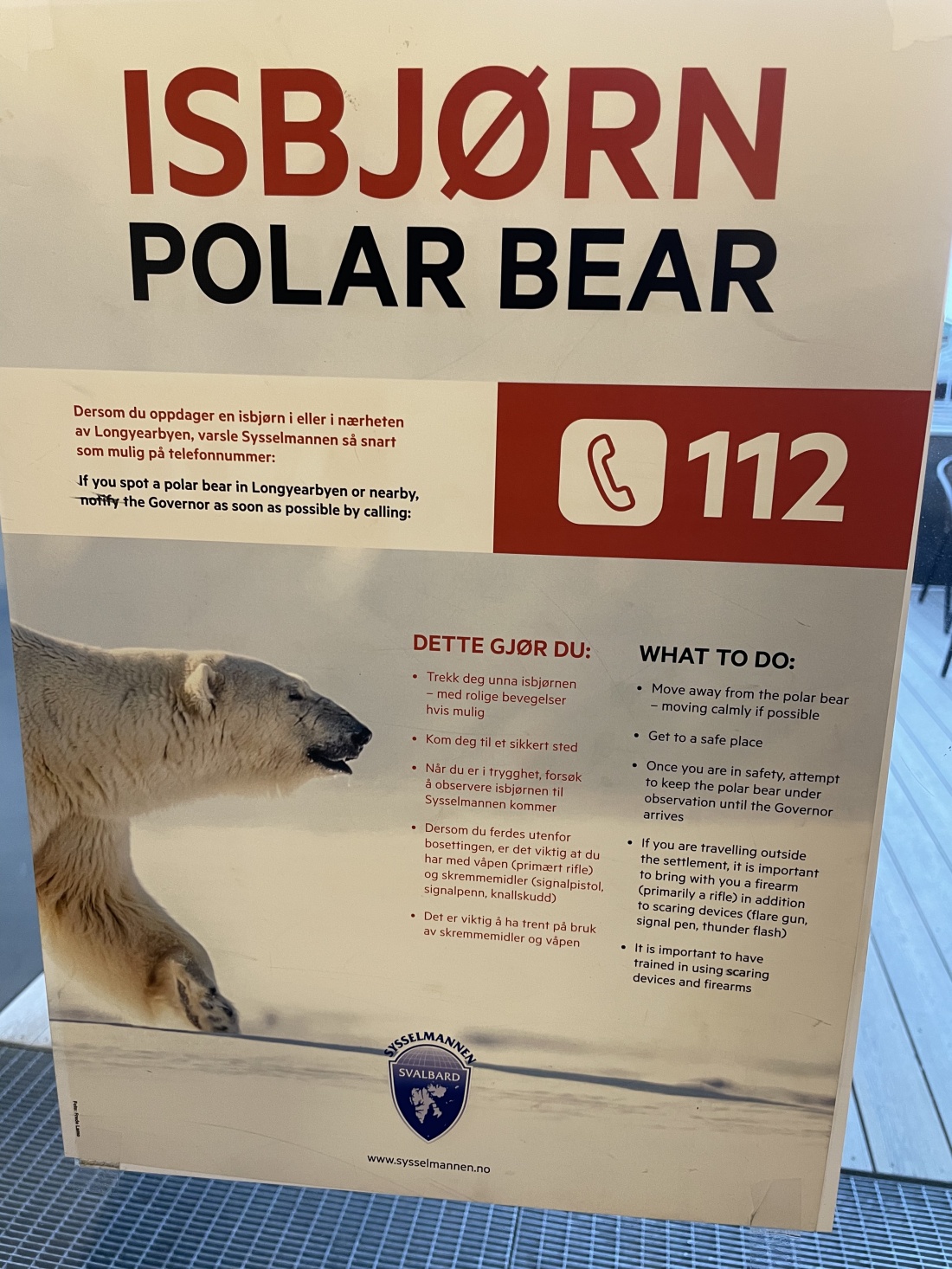

Yet if the risk cannot be eliminated, it can be hugely reduced by proper practice. Svalbard has some of the strictest human / bear interaction laws in the world. In practice, if you as a visitor want to explore, it will be in the company of a local guide with a firearm, flares and thorough training how to avoid a disaster.

Would Yellowstone or Jasper ever accept those restrictions on its tourists? Probably not; their black and grizzly bears are much less predatory than polar bears, and their culture much more permissive. There have been a few incidents in Spitsbergen over the years, including an attack in the campground just outside Longyearbyen. In response, it is now ringed by electric fencing but locals suspect would it not deter a determined bear. Hopefully, we will never have to find out.

But if the bears are often on one’s mind, it’s something quite different that is generally filling one’s ears.

Dogs, like polar bears, are indivisible from the Arctic. They are postcards from the Pleistocene – the epoch in which we first began to carve them from wild wolves. It seems oddly fitting that they became part of explorers’ attempts to investigate the north, via these islands and ocean where the Pleistocene has never quite ended.

A land carved by ice never forgets. Back in England, our coast, caves and even our river networks are riddled with the Pleistocene’s fingerprints. Ten thousand years, and still they show it.

I am grateful to have had the opportunity to travel north to understand their past a little more.

Svalbard: Diet of Rocks

Mid-October

What would reindeer be without Father Christmas? Just another miracle from the north perhaps; they certainly have a firmer grip on the ice than the man with the sleigh and presents, who after all is based on a Turkish saint. Semi-domesticated reindeer roam widely across continental Scandinavia, but Svalbard hosts a unique subspecies, and it is as wild as the mountains and drifting snow.

And dumpy, somehow; wide, rounded and plump. Filled with heat-conserving fat though they may be, these are the smallest of all reindeer subspecies, hardly taller than a roe deer although much heavier. I have seen reindeer in the wild once before – woodland caribou in a Canadian Rockies herd that has now gone extinct – and can imagine them, perhaps, roaming the North Downs in the Pleistocene, leaving their disproportionately enormous hoofprints on snowy hills. Like the Arctic fox, they were residents of Britain in its colder times.

Today, they personify the polar circle and the boreal forest that flanks it. In Svalbard, they can be found anywhere not capped by glaciers.

Reindeer are the only deer species where females sport antlers. This mother, with her calf behind her, is coming into velvet – she will use her antlers throughout the winter to defend food patches against rivals.

And there is food, remarkable though it may be on islands that largely look like this.

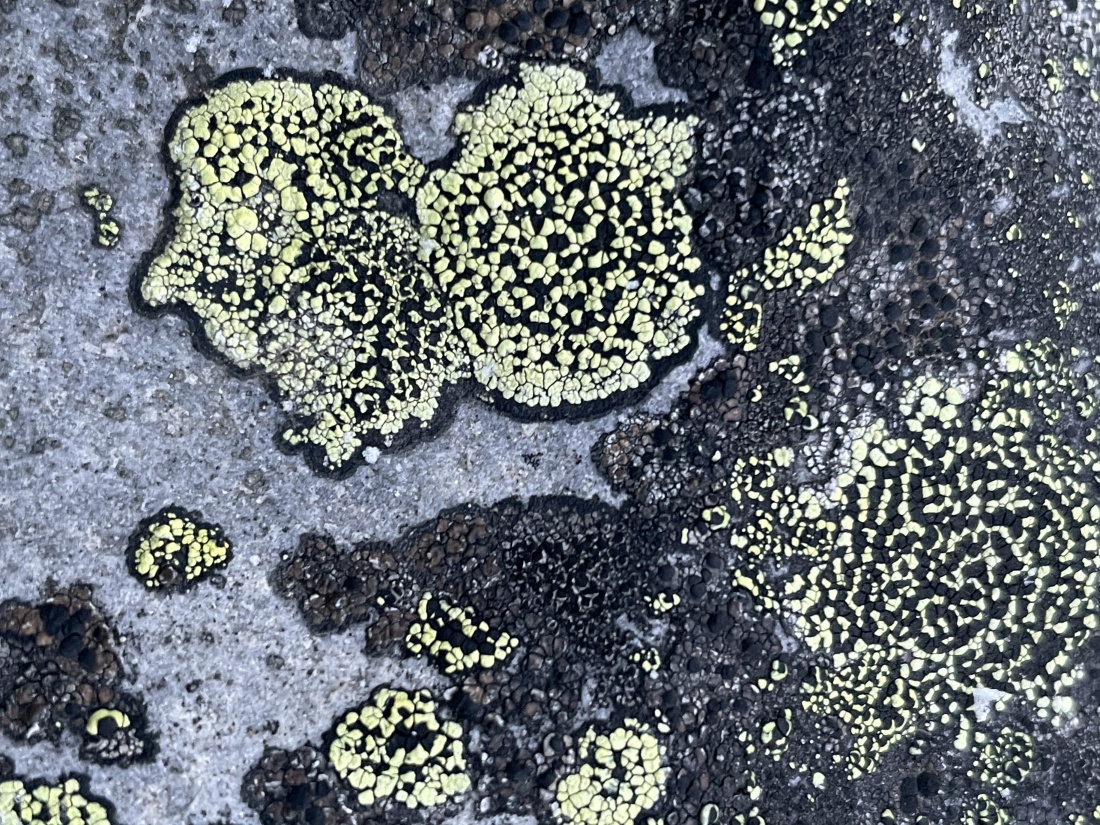

In summer, Svalbard supports a rich community of polar wildflowers: purple saxifrage, Arctic poppies and Alpine bistort. But in winter, reindeer survive on mosses, grasses and tough plants such as polar willow. In much of their global range they browse on lichens, but not in Svalbard; lichens here are short and tough, like this map lichen, a species that can live for thousands of years.

Reindeer do not, although a few make it into their teens. On an archipelago with no wolves, starvation during spring their biggest threat. Very occasionally, a polar bear might try its luck, but the white bear is better equipped to tackle marine prey.

So for the most part, reindeer are preoccupied with quietly grazing amongst the rocks.

And blending in so well, a casual glance might fail to spot them. Two reindeer below.

Svalbard: Life on Ice

Sunburst lichen

An Arctic fox is one thread in a web. But unlike the complex ecosystem that a red fox can navigate and exploit, the far north offers less prey and fewer rivals.

There are no native rodents in Svalbard; a few sibling voles Microtus levis live near the old Soviet mining settlement of Grumantbyen, but they were accidentally introduced in hay in the 1960s, and do not appear to be spreading. So any mammals that the fox is able to consume are likely to be killed by weather, starvation or polar bears. But they do have birds – one of which is hardy enough to stay all year.

This is the rock ptarmigan, found widely around the northern hemisphere but of particular importance to Svalbard and its foxes. This impossibly white bird turns mottled brown in the summer, much like the fox itself.

Other birds linger with the last of the light. This purple sandpiper is wearing leg rings from a research project. They overwinter on the shores of Europe and the UK.

Plants have no such options, and can only time their activity with the seasons. Most of the cotton-grass has finished by mid-October, but this one clings on, bobbing in the clean air like a rabbit’s tail.

Like the trees, it will be under snow soon. Yes, this is Svalbard’s tree: polar willow, which grows 2 – 5cm high.

That is about the same depth as a polar bear’s coat.

Svalbard: The Fox of Our Past

Mid-October

Creswell Crags, Derbyshire. Much of Britain is hollow: where the land is limestone, rivers and rain carve out sprawling, dripping caves. Unconscious diaries of our past, caves faithfully record people, climate – and wild things. Some of the wildest, and some of the hardiest.

This is the jawbone of an English Arctic fox unearthed at Creswell.

This animal trotted through hills that did not sport moors, blanket bogs or pastures. The Arctic fox’s England – or the peninsula soon to become England – must have looked more like this.

The Arctic fox is a living thermometer. When the ice sheets crept southwards, the fox came with them. As the climate warmed, its range contracted north, and the red fox – larger, less cold-adapted – took over.

The Arctic fox is a living thermometer. When the ice sheets crept southwards, the fox came with them. As the climate warmed, its range contracted north, and the red fox – larger, less cold-adapted – took over.

But the Pleistocene seems current news in Svalbard.

October is a black-and-white movie in Spitzbergen, largest of the Svalbard islands and home of the 25 miles of road that make up the archipelago’s entire road network. The slopes rise without apology to impossibly twisted crags that tower over loose black rocks speckling the snow like pepper. How can any fox live in such a place? No rodents, no berries; in summer they hunt seabirds, but in this season, their menu is only ptarmigan and reindeer carrion, and whatever scraps the polar bears might leave.

They blend into the landscape as if they are built from it. Hiding from the wind, watching themselves be watched. If they do not move, they are almost invisible – yet there is one in the photo below.

Arctic fox. I have waited a long time for this.

On an island far beyond reach of red foxes rests their cousin, equipped with fur that more than doubles in density during the winter, and feet pads that retain warmth through complex blood vessels. Its tiny ears are built to prevent heat leakage, and its small body size requires fewer calories. Its trick of moulting between brown summer fur and the ghostly winter garb means that it is never easy to spot.

Yet I still find it impossible to stare at these vast rocky valleys and not think it a miracle that they can eke a living.

A fox like this knew an England now written in our caves. I hope many generations of its progeny leave footsteps in Arctic snow.

Svalbard: Top of the World

Mid-October

Yesterday, I was in the Holocene. That is our epoch, the historical epoch, the thousands of years after the last ice age which we refer to as recorded history.

But I’ve left it. I’ve landed where ice still rules.

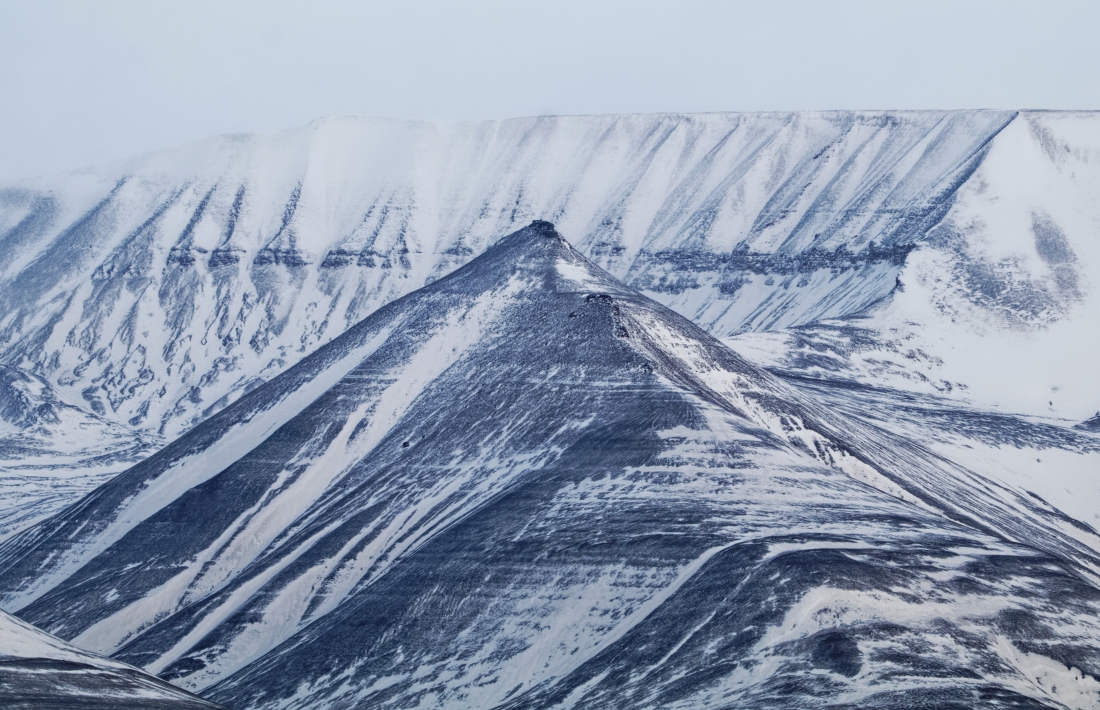

Svalbard: “cold coast” in old Norse. This is an a cappella of wilderness – just the raw beats of nature, no trees higher than a human thumb, no raging riot of colour save when lichens and purple saxifrage defy the snow. It is quiet, finely-whittled, and artistic. It is cold, clean and stern. It is terrifying, grand and magical. It is an emissary of the North Pole, which lies on its frozen ocean only a few hundred miles beyond Svalbard’s icecaps and shallow braided rivers.

You cannot see the pole from Svalbard, obviously, but you are always aware of it, for its weather breathes on you, and on the mountains.

Svalbard is the edge of everything. At nearly 80° north, Longyearbyen is above all of Alaska and most of Greenland and Canada, and far remote from the European mainland. This community of 2000 souls is not only the most northerly town in the world, but holder of a fistful of ‘most northern’ records: of a community church, of a commercial airport, museum, university – and of sunlight, too, in this season, for in autumn the polar night marches south from the pole.

I’ve seen the quickfire twilight of the tropics. The High Arctic styles it instead with careful slowness; you can watch the glow for 45 minutes and see little change. But the sun sets on 26th October, and then does not rise at all until mid-February. Polar Night is the Arctic’s price for Midnight Sun.

Under sun or northern lights, ice is everything. Glaciers here are not ornaments on distant mountains – they are neighbours which share the valley.

Huge areas of Svalbard are under icecaps and glaciers, and even those that are not are held in permafrost’s iron grip. Some areas are frozen down to over 400 metres. It is no country for putting infrastructure underground, so water pipes snake around the town wrapped up with insulation.

So remote is this island that the global seed vault shelters on it, guarding a backup supply of the world’s crop samples against all disasters.

Life dormant inside the vault; life leaving footprints in the snow outside it. This island hosts some very special wild things. I’ve travelled north with aspirations of finding them.